During World War I, a soldier discovered his friend, wounded, had fallen between the trenches out in “no man’s land.” Ignoring his officer’s orders, he dashed from the safety of the trench to try to rescue his friend. He returned mortally wounded with his friend on his shoulder, now dead.

The officer was angry. “I told you not to go. Now I have lost both of you. It wasn’t worth it!”

The dying soldier replied, “But it was Sir, because when I got to him, he said, ‘Jim, I knew you’d come!’“

Out there is the devil’s no man’s land, our friends are harbouring a secret, often unrealized hope, that we will come with some rescue from an ever-increasing hopelessness.

There are no seasons to the search – it goes on around the clock throughout the calendar. No one is excused from the task. All are commanded to go. I don’t know what reasons you might conjure up for not going or for the possibility of failure. All I know is that your friends are “out there” wounded, dying, waiting. Will you hear them say, “I knew you’d come”?

Derived from a story by Douglas F. Parsons

One of the most problematic aspects of combat casualty care is moving the casualty, especially considering the larger tactical situation. While issues like hemorrhage control, which treats the leading cause of preventable combat death, are being addressed with new technologies and emphasis in tactical first aid training, casualty movement usually does not get nearly the attention or the innovation that it deserves considering its importance. Casualty’s injuries and the treatment provided will vary from casualty to casualty, but their requirement to be moved will always remain a constant. Not every casualty will require hemorrhage control but every casualty at some point will need to be moved. If firepower is preventative medicine, then casualty movement is essentially definitive care. Every movement of the casualty, from point of injury (POI) should be made in an effort to get them one step closer to definitive care while not further endangering you, the casualty, team members or the mission in the process.

Not every casualty will require others to move them. Though, it should go without saying, casualties that can ambulate themselves should remain in the fight, provide self-rescue and self-aid. Casualties that are deceased should be low priority for movement and no attempt to move them until absolutely safe to do so. Those that cannot move on their own will at some point require to be moved. Deciding when and how it is appropriate is the key decision.

It must be both a tactical and a medical decision on when it is appropriate to move a casualty. Tactical considerations must be made regarding balancing resource distribution to the appropriate task at that given time (e.g. casualty rescue vs. assault/security) and risk management (e.g. is it worth risking resources to rescue a casualty if the attempt may lead to further casualties). Medical considerations must be made regarding the urgency of rescue and/or evacuation (will the casualty die if we do not rescue them right away?). Both the tactical and the medical considerations then need to be balanced to decide the appropriate action for the greater good of the mission, the team and the casualty. These decisions will need to be made by commanders or leaders on the ground with input from any medical authorities available, which doesn’t necessarily have to be a medic, but the decision will need to be made quickly. The ability to determine injury severity from a distance is difficult and ‘medicine across a barrier’ is a unique skill set that should be practiced by the medic. Optics can aid in distant assessments to determine if the casualty is salvageable.

It makes sense that those whose job it is to treat casualties be the subject matter experts in casualty movement, however no medic will be able to perform this task on their own, and sometimes shouldn’t perform it at all. It is not an appropriate use of resources to utilize a medic in a dangerous rescue. This once again creates a tactical problem as well as a medical problem. Not only has the commander lost the casualty from the mission, but now resources other than the medic must be dedicated to managing this casualty. The medic will usually not be able to move a casualty by themselves. This means it is essential that all team members be proficient in casualty movement techniques and commanders must be cognizant of the realistic logistics and effort involved in this task.

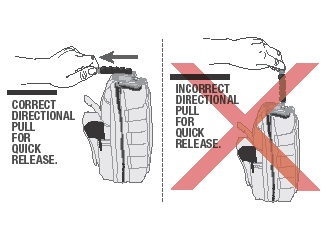

From a resource management perspective, casualty movement is logistically intense. Practicing and streamlining casualty movement techniques is essential to maximize efficiency of resources and energy. It is important to be able to move a casualty as fast and as safe as possible, with the least amount of resources, in the shortest amount of time, to the most appropriate location.

There are three phases in which a casualty will require to be moved. Each is unique and generally correlates with its respective phase of Tactical Combat Casualty Care, though there are slight differences. The three phases of casualty movement are:

- Tactical Rescue Phase

- Tactical Casualty Movement Phase

- Tactical Evacuation Phase

Each phase presents its own unique problems that must be overcome for effective casualty movement.

Stay tuned to the continuation of Tactical Rescue…

ctoms.ca