January 4, 2013

by Chris

0 comments

I usually try to refrain from writing about tourniquets. The topic is overdone, and rightly so. The data certainly support’s its hyper use in tactical medicine. I’m not anti-tourniquet, rather the contrary. It’s just that the information and misinformation available on them can be overwhelming so I try to refrain from contributing to it. I have my opinions and personally try to stick to published papers, disregarding the rest. Tourniquet marketing sickens me. A few weeks ago at the SOMA conference I saw even more new tourniquets on the market, plus the same usual suspects, all fighting for a tiny piece of the pie. In my opinion all these new tourniquets confuse the end user by clouding the waters. It dilutes standardization and puts more untested product out there. Buyer beware! But to the point…

I thought I’d talk a little bit about my experience with tourniquets so that you can learn from my mistakes, finishing with a summary of some of the most current data.

Here’s a little history lesson:

In 1996 TCCC was born with Butler’s paper. Unfortunately that didn’t really catch on due to a general resistance to change within human nature and a lack of requirement – no war. Fast forward to 2001 during preparations for my Afghanistan deployment, trickles of TCCC would infiltrate our training in the form of a general overview briefing on the topic. The take home point: contrary to everything you’ve been taught, tourniquets are a priority in combat.

So, armed with this new information, my civilian EMT certification, and an elastic IV tourniquet that I got from a medic buddy, I packed my ‘IFAK’ (though the term wasn’t used until years later). Now understand that in 2002, a CF IFAK was two small pillows called Field Dressings circa 1952! Having pride in my EMT qualification as an infantryman, I got an old Jungle First Aid Kit Pouch, probably from the same medic buddy, and stuffed it full of what I though was important at an EMT level, including my little elastic tourniquet. The C-A-T® and SOF-TT hadn’t even been invented yet.

Fast forward to the night of 17 April, 2002 and I’m kneeling beside one of the best and strongest Sgt.’s in the Battalion, and a friend of mine at that. It’s night in the desert on a sandy slope of a wadi. In the dim light of my headlamp and the burning helmet cover that lay beside us, I’m digging in my ‘IFAK’ for my ‘tourniquet’ because that is all I remember from the briefing. Staring back at me is a hole in my friend’s leg larger than my fist, steadily soaking the sand and all the dressings we throw at it with blood.

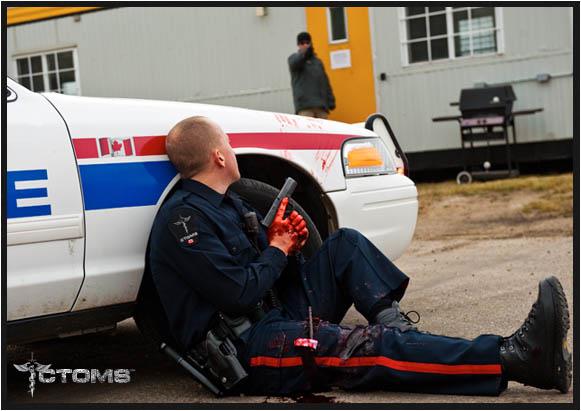

My medic friend joins me. He’s closer to his leg so I pass my tourniquet to him and tell him to put this on. He says he thinks we should try direct pressure first. He’s the boss, so I pack my tourniquet away. I go look for other casualties in the dark chaos and finding none so I make my way back to the original casualty. At this point, the medic agrees it’s time to try the tourniquet. So I dig it out again, pass it off, and history is made. It was the first application of a tourniquet to a Canadian Forces soldier, by a Canadian Forces soldier probably since the Korean War. But there were some hard lessons learned.

The first tourniquet applied to a CF soldier, by a CF soldier since the Korean War.

The Sgt. lived despite, unbeknownst to us, our best efforts to the contrary. Read that sentence again. It’s actually pretty heavy to personally come to that realization. That tourniquet didn’t have a hope in hell of ever stopping arterial flow in his muscular thigh. A venous tourniquet, meaning a tourniquet applied tight enough to stop all venous blood return to the core, but still allow arterial blood into the limb (and out the wound) can very easily kill a casualty. And if it doesn’t kill them, I believe this is where the dogma of ‘tourniquet on a limb means you lose the limb’ came from, it can create a compartment syndrome and speed tissue necrosis much faster than a properly tightened tourniquet. What saved the Sgt. was a rapid MEDEVAC and short time from injury to surgery. As I said, a hard lesson learned, very early in the war. So what’s happening these days?

If you don’t read the JSOM, you should. Winter 2012 edition has a published retrospective study called Forward Assessment of 79 Prehospital Battlefield Tourniquets Used in the Current War. This is what it says: 79 tourniquets applied to 65 limbs on 54 combat casualties were studied. Now here’s the eyebrow raiser: 54 of the 65 limbs or 83% arrived at the forward surgical team WITH a distal pulse, and 11 of the 65 had no distal pulse. Of the limbs with the effective tourniquets applied (no distal pulse), half of them (5) had return of pulse upon release of tourniquet. And of all the injuries, only 17 of all 65 limbs actually had injuries requiring a tourniquet. Now that last point is not as important. In combat it is better to apply a tourniquet when in doubt than to risk missing a life threatening bleed. The data supports this rule. But the rest of the data is telling us something important; tourniquets are either not being tightened enough, or they are coming loose during transport. Chew on that and come up with your own solutions. It’s a problem.